Monday 4.7. 19

That's the length of a python

-- with 73 eggs!!! -- that scientists caught in

the Florida Everglades

GENDER MARKETING

REMEMBER: YOU HAVE A MATCHING QUIZ ON PERSUASIVE TECHNIQUES ON FRIDAY. (this is a homework grade)

Assignment:

1) look through the gender marketing images below.

2) Watch: The world in pink and blue (7:30)

3)Watch: Moshino Barbie (:30)

4) Read: Position and Image Creation

5) Read: Atlantic Monthley article:

Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago

6) Respond to the following: From what you have read and watched, discuss to what extent advertising is a reflection of a society and can it possibly impact social change? Do you note any parallels with social media platforms?

Incorporate information from both the videos and the articles into your response.

use an MLA headingsize 12, Times New Roman font

double spacing

minimum 300 words

include internal citations and Works Cited

Cite as follows within the response: (Pink and Blue), (Moshino), (Sweet), (Bahsous, Rolla). Use the following for a Works Cited:

Bahsous, Rolla. “Gender Marketing: How Brands Use the Power of Colors To Persuade You.” SuperMoney!, 5 Feb. 2019, www.supermoney.com/2014/08/colors/.

checkoutabctv. “GENDERED MARKETING | The Checkout.” YouTube, YouTube, 17 Apr. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=3JDmb_f3E2c&t=7s.

Sweet, Elizabeth. “Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 9 Dec. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/12/toys-are-more-divided-by-gender-now-than-they-were-50-years-ago/383556/.

Sweet, Elizabeth. “Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 9 Dec. 2014, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/12/toys-are-more-divided-by-gender-now-than-they-were-50-years-ago/383556/.

YouTube, YouTube, www.youtube.com/results?search_query=moschino%2Bbarbie%2Bcommercial.

7) The assigment is due on Monday, April 8

8) This quarter's grades close on Friday, April 12. No work will be accepted after 3 pm that day

*********************************************

#2) Pink and Blue: link in assignment instructions

#3 Moshimo Barbie: link in assignment instructions

#4) read the following:

Positioning and Image Creation

Many companies rely on advertising to sell their image, product, and brand. As contemporary semioticians (those who study signs, referents, and meanings) note, advertisers use two main techniques to sell products or brands: positioning and image creation.

Positioning refers to having a defined targeted market for a brand or product. Image creation are the personality/characteristics attributed to the product or brand visually. This is where colors become useful and why they are carefully chosen by design teams. The use of color provides a non-verbal signal that helps persuade us that we, as consumers, need to buy this or that product or brand. (O’Shagnessy and Stadler).

Colors are powerful, not only because they become associated with a brand logo or image, but because of the connotations society attaches to them. Apart from the statement “It’s not for women” in the diet soda ad above, what makes it manly?

Gender Specific Colors: Pink is for Girls!

It is hard to not associate blue with boys and pink with girls, from infancy to adulthood. Walk through any toy store and you’ll find an aisle or two packed to the gills with pink-dressed baby dolls, dollhouses and costumes. An aisle over, you’ll find toy trucks, guns, building blocks and toy soldiers in hard colors like black, blue, green and red. Parents will find pink and purple outfits for their little girls and blue and green outfits for their boys.

It’s gotten to the point that if a girl is put in “baby boy blue” she’s easily mistaken for a boy, and vice versa. And funny enough, gender neutral colors like cream and yellow are only making it worse.

Color Stereotypes Haven’t Grown Up

Color stigmas and stereotypes continue well into adulthood. Cosmetic brands design their female-targeted products with the same delicate hues, though perhaps a little sleeker. Shiner purple, hotter pinks, for example. Male products often contain bolder colors like black and blue, to appeal to men as more “masculine” and “strong.”

Fragrances are a great example of this. When was the last time you saw a perfume bottle in a striking black, or a cologne with pink and sparkly embellishments?

Another example, shaving tools and creams. Take a walk through any personal hygiene department and you’ll find little pink razors packaged with flowery graphics, sparkles and even clouds. A few steps farther, you’ll see black razors with grey packaging and straight lines, no frilly graphics in sight. You might even find that comparable razors from the same company, one for “her” and the other for “men,” cost differently, with the pink razor costing slightly more. New monthly subscription service Dollar Shave Club calls this the Pink Tax.

Why Does Color Marketing Work?

Most will look at the graphic above and agree with the colors and their associated emotions and logos. Yellows convey warmth, happiness, and clarity, and are prominent in Subway, Denny’s and Sprint’s marketing. On the other end of the spectrum, shades of gray show neutrality and calm, like the Apple and Wikipedia logo.

For many, that’s the end of the conversation. Pink appeals to women because it’s girly, black and blue to men because they’re strong. Marketing departments have figured out the formula, it’s been instilled in us as consumers since before we even knew anything about colors, and that’s just the way it is.

Gregory Ciotti from Help Scout dismisses this idea swiftly, and calls it a vapid conversation “about as accurate as your standard Tarot card reading.”

“…in regards to the role that color plays in branding, results from studies such as The Interactive Effects of Colors show that the relationship between brands and color hinges on the perceived appropriateness of the color being used for the particular brand (in other words, does the color “fit” what is being sold).The study Exciting Red and Competent Blue also confirms that purchasing intent is greatly affected by colors due to the impact they have on how a brand is perceived. This means that colors influence how consumers view the “personality” of the brand in question (after all, who would want to buy a Harley Davidson motorcycle if they didn’t get the feeling that Harleys were rugged and cool?).” (Help Scout)

How well would a pale pink and bedazzled Harley sell? Because the Harley Davidson brand’s personality is perceived as rugged, tough, classic and cool, probably not all that well.

Likewise, a dark gray Venus razor with a straight, not fancifully curved, handle would likely confuse female consumers. It wouldn’t attract male users because of the perception and connections made with Venus razor and femininity. So what did Gillette do? They produced the same razor in black and green, but called it Gillette Body. They also nixed the “passion,” “embrace,” and “sensitive” terminology and instead put “engineered.” Because science.

Take a second to remember the Bic Cristal Pen for Her, not to be confused with a pen used for writing down actual thoughts and knowledge, but one used for drawing pretty things and being delicate.

Masculine Branding to Appeal to Women

We all know that brands that promote anti-aging products will often use jargon that sounds scientific to persuade the average consumer that their products will get rid of wrinkles. And because many beauty products rely on universal myths, like the quest for youth and sexual attractiveness, these products are extra popular.

But why aren’t these products packaged in more feminine colors? Why are anti-aging products targeted at women (like Olay’s Regenerist anti-wrinkle line) packaged in reds, grays or dark blues? Aren’t these colors are usually associated with masculinity?

Anti-aging brands use colors associated with masculinity in order to persuade their consumers that they can also associate their brand with authority and power. After all, their products are supposed to be scientifically-proven to work. Again, science and facts are connected to masculine colors. Would these anti-aging products have the same effect if they were packaged in light purple hues? Probably not.

Metrosexual Marketing: Are You as confused as we are?

Taking a step back from associating brands with specific genders and personalities, let’s look at gender-specific products themselves, like facial moisturizer and mascara.

In her article “Real Men Do Wear Mascara: Advertising Discourse and masculine identity,” Claire Harrison examines the rise of the metrosexual economy in the past 10 years by examining the advertising and branding of male mascara – what L’Oreal calls, “Manscara.”

Harrison notes that male mascara is given traditional masculine qualities, such as efficiency and speed, emphasized in the slogan, “Two strokes and you’re out!”.

The colors used in the packaging and advertising of these male mascaras are powerful and authoritative colors like black and red, in order to persuade male consumers that this product is still masculine.

And like female-targeted anti aging creams, L’Oreal’s “Men Expert” line puts the focus on science, expertise, and masculine logic.

The manly branding works to lure in the male consumer, despite the feminine connotations of beauty products, and make them conscious of their appearance. What do most people do when they’re feeling self-conscious? They buy things.

The Impact of Color and Design in Marketing

“In an appropriately titled study called Impact of Color in Marketing, researchers found that up to 90% of snap judgments made about products can be based on color alone (depending on the product).” (Help Scout)

Combine color combinations in marketing with an individual’s cultural background, upbringing, and shopping preferences and you’ve got the perfect recipe for a color-guided shopper.

One could say that the color argument boils down to gender identity and insecurity. Will this product make me more attractive? Is this popular with others in my peer group? Will it help me fit in? Is this pretty, flirty, sexy? Will this make me appear strong, manly, and also sexy?

A final factor in the argument for color and design marketing is how men and women shop. Generalizing, of course, a woman is more likely to stop and consider their options when shopping, study the packaging, and find value in the appearance of the final product. Male shoppers keep it simple, grabbing the staple items they use and scurrying out of the store as fast as possible. In fact, most men don’t even notice the packaging (unless it’s pink), just the brand name and where it usually sits on the shelf. After all, men buy, but women shop.

What do you think about color-based marketing? Do you feel your shopping habits are influenced by packaging and colors? Is it a necessary evil for the marketplace?

This article was written by staff writers Rolla Bahsous and Brenda Harjala.

Bahsous, Rolla. “Gender Marketing: How Brands Use the Power of Colors To Persuade You.” SuperMoney!, 5 Feb. 2019, www.supermoney.com/2014/08/colors/.

********************************************************************************##5 From the Atlantic Monthly

Toys Are More Divided by Gender Now Than They Were 50 Years Ago

Even at times when discrimination was much more common, catalogs contained more neutral appeals than advertisements today.

When it comes to buying gifts for children, everything is color-coded: Rigid boundaries segregate brawny blue action figures from pretty pink princesses, and most assume that this is how it’s always been. But in fact, the princess role that’s ubiquitous in girls’ toys today was exceedingly rare prior to the 1990s—and the marketing of toys is more gendered now than even 50 years ago, when gender discrimination and sexism were the norm.

In my research on toy advertisements, I found that even when gendered marketing was most pronounced in the 20th century, roughly half of toys were still being advertised in a gender-neutral manner. This is a stark difference from what we see today, as businesses categorize toys in a way that more narrowly forces kids into boxes. For example, a recent study by sociologists Carol Auster and Claire Mansbach found that all toys sold on the Disney Store’s website were explicitly categorized as being “for boys” or “for girls”—there was no “for boys and girls” option, even though a handful of toys could be found on both lists.

That is not to say that toys of the past weren’t deeply infused with gender stereotypes. Toys for girls from the 1920s to the 1960s focused heavily on domesticity and nurturing. For example, a 1925 Sears ad for a toy broom-and-mop set proclaimed: “Mothers! Here is a real practical toy for little girls. Every little girl likes to play house, to sweep, and to do mother’s work for her":

Such toys were clearly designed to prepare young girls to a life of homemaking, and domestic tasks were portrayed as innately enjoyable for women. Ads like this were still common, though less prevalent, into the 1960s—a budding housewife would have felt right at home with the toys to “delight the little homemaker” in the 1965 Sears Wishbook:

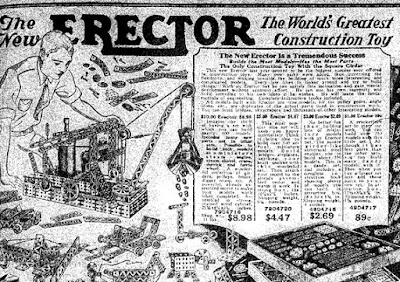

While girls’ toys focused on domesticity, toys for boys from the '20s through the '60s emphasized preparation for working in the industrial economy. For example, a 1925 Sears ad for an Erector Set stated, “Every boy likes to tinker around and try to build things. With an Erector Set he can satisfy this inclination and gain mental development without apparent effort. … He will learn the fundamentals of engineering”:

However, gender-coded toy advertisements like these declined markedly in the early 1970s. By then, there were many more women in the labor force and, after the Baby Boom, marriage and fertility rates had dropped. In the wake of those demographic shifts and at the height of feminism's second-wave, playing upon gender stereotypes to sell toys had become a risky strategy. In the Sears catalog ads from 1975, less than 2 percent of toys were explicitly marketed to either boys or girls. More importantly, there were many ads in the ‘70s that actively challenged gender stereotypes—boys were shown playing with domestic toys and girls were shown building and enacting stereotypically masculine roles such as doctor, carpenter, and scientist:

Although gender inequality in the adult world continued to diminish between the 1970s and 1990s, the de-gendering trend in toys was short-lived. In 1984, the deregulation of children’s television programming suddenly freed toy companies to create program-length advertisements for their products, and gender became an increasingly important differentiator of these shows and the toys advertised alongside them. During the 1980s, gender-neutral advertising receded, and by 1995, gendered toys made up roughly half of the Sears catalog’s offerings—the same proportion as during the interwar years.

However, late-century marketing relied less on explicit sexism and more on implicit gender cues, such as color, and new fantasy-based gender roles like the beautiful princess or the muscle-bound action hero. These roles were still built upon regressive gender stereotypes—they portrayed a powerful, skill-oriented masculinity and a passive, relational femininity—that were obscured with bright new packaging. In essence, the "little homemaker" of the 1950s had become the "little princess" we see today.

It doesn’t have to be this way. While gender is what’s traditionally used to sort target markets, the toy industry (which is largely run by men) could categorize its customers in a number of other ways—in terms of age and interest, for example. (This could arguably broaden the consumer base.) However, the reliance on gender categorization comes from the top: I found no evidence that the trends of the past 40 years are the result of consumer demand. That said, the late-20th-century increase in the percentage of Americans who believe in gender differences suggests that the public wasn’t exactly rejecting gendered toys, either.

While the second-wave feminist movement challenged the tenets of gender difference, the social policies to create a level playing field were never realized and a cultural backlash towards feminism began to gain momentum in the 1980s. In this context, the model outlined in Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus—which implied that women gravitated toward certain roles not because of oppression but because of some innate preference—took hold. This new tale of gender difference, which emphasizes freedom and choice, has been woven deeply into the fabric of contemporary childhood. The reformulated story does not fundamentally challenge gender stereotypes; it merely repackages them to make them more palatable in a “post-feminist” era. Girls can be anything—as long as it’s passive and beauty-focused.

Many who embrace the new status quo in toys claim that gender-neutrality would be synonymous with taking away choice, in essence forcing children to become androgynous automatons who can only play with boring tan objects. However, as the bright palette and diverse themes found among toys from the ‘70s demonstrates, decoupling them from gender actually widens the range of options available. It opens up the possibility that children can explore and develop their diverse interests and skills, unconstrained by the dictates of gender stereotypes. And ultimately, isn’t that what we want for them?

********************************************************************************

#6 Written response to the watched / read materials above.

No comments:

Post a Comment